A Gentle Introduction to Perspective

A lot of students find perspective difficult. This isn’t unexpected, because most sources actively try to be as confusing as possible.

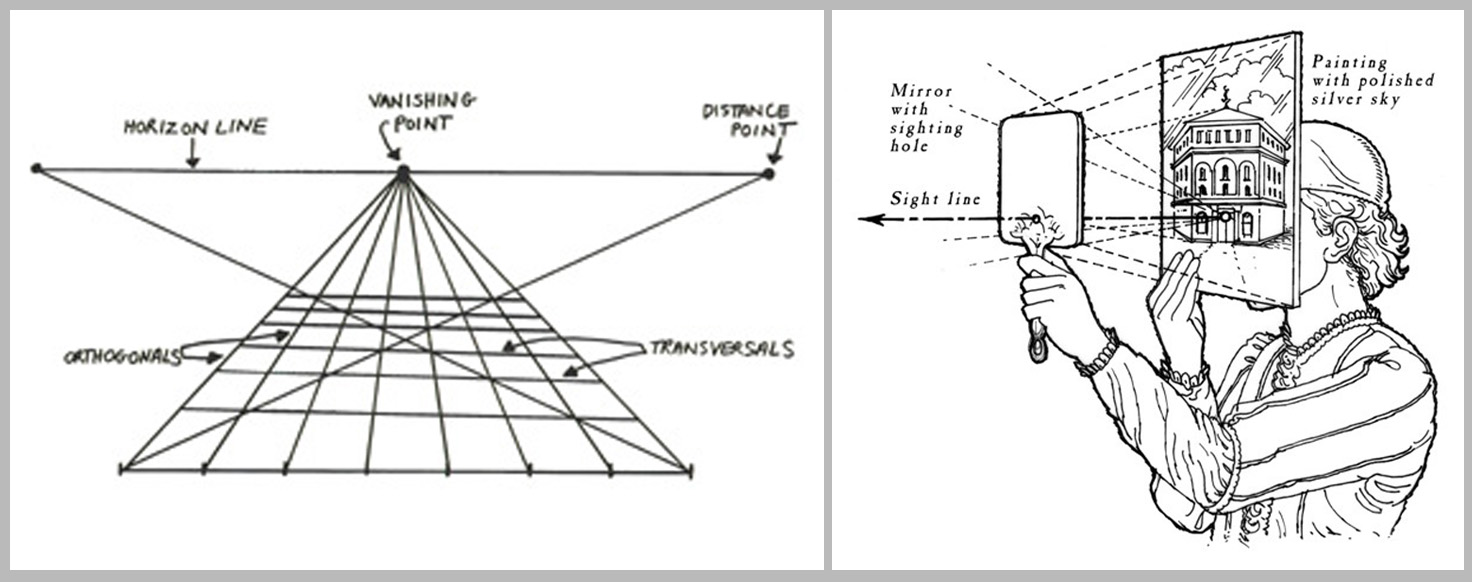

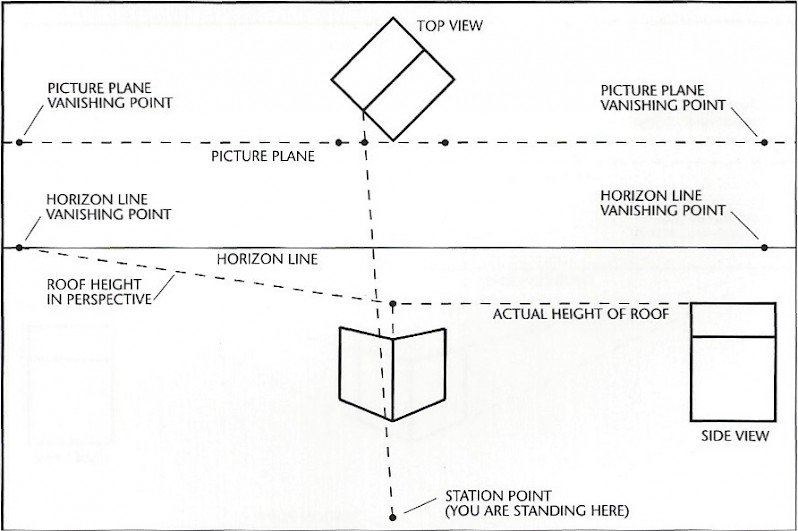

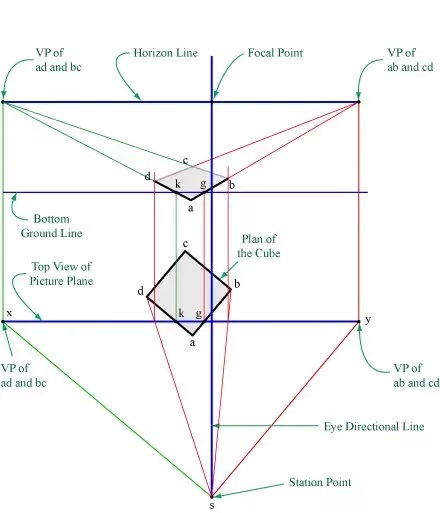

Just look at some of these “helpful” diagrams:

This stuff…

…HURTS…

…to look at.

I swear that whoever drew these diagrams made them as complicated as possible on purpose in order to pump their ego. They’re the worst. It’s impossible to learn anything from them.

When I was learning this material it was a total slog and it left me with massive headaches. However, it’s really not as bad as the diagrams make it seem. A lot of it is common sense. Coming from my personal teaching experience as well as some informal focus testing, I’ve put together what I consider a comprehensive, sane explanation of perspective.

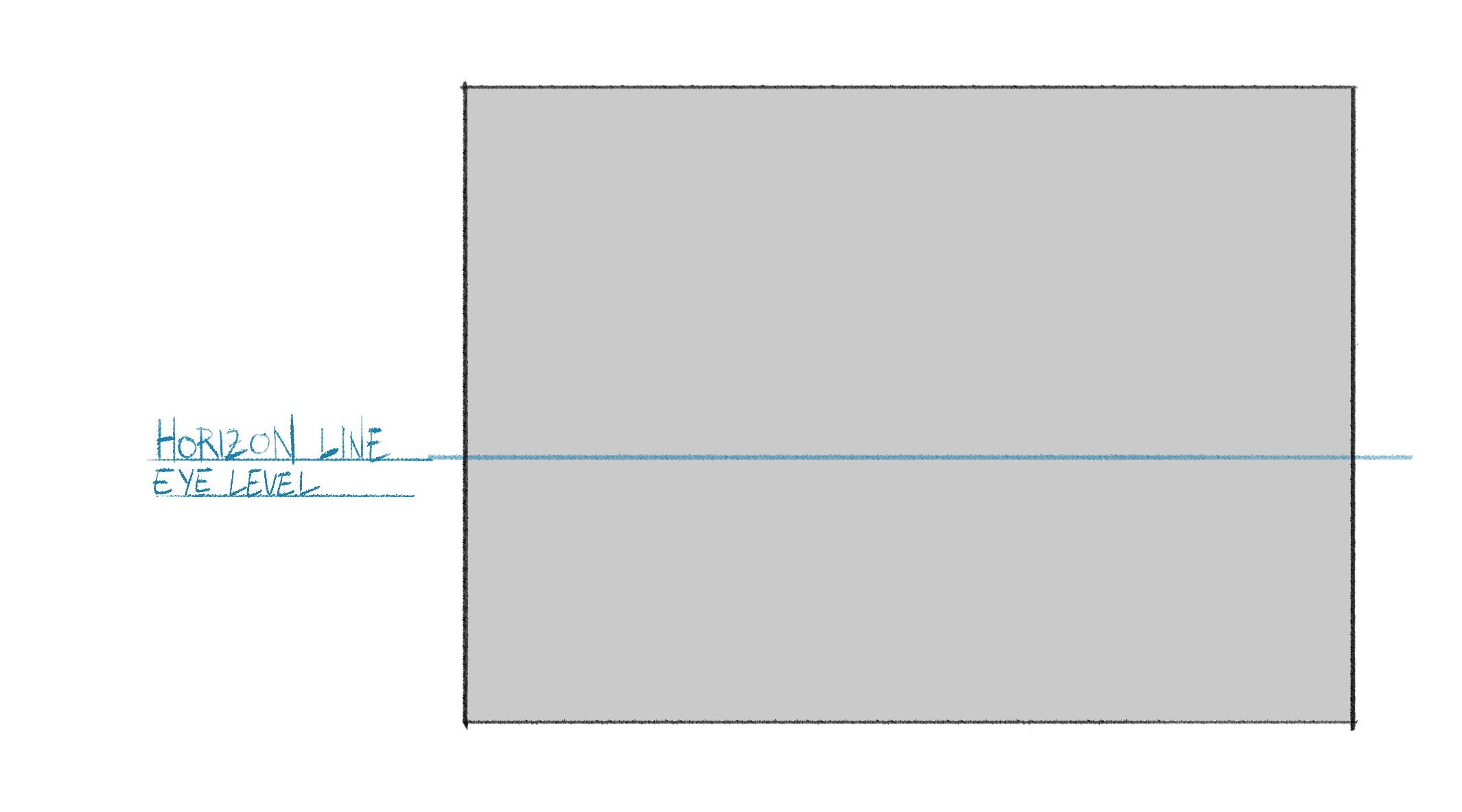

Let’s start with the horizon line.

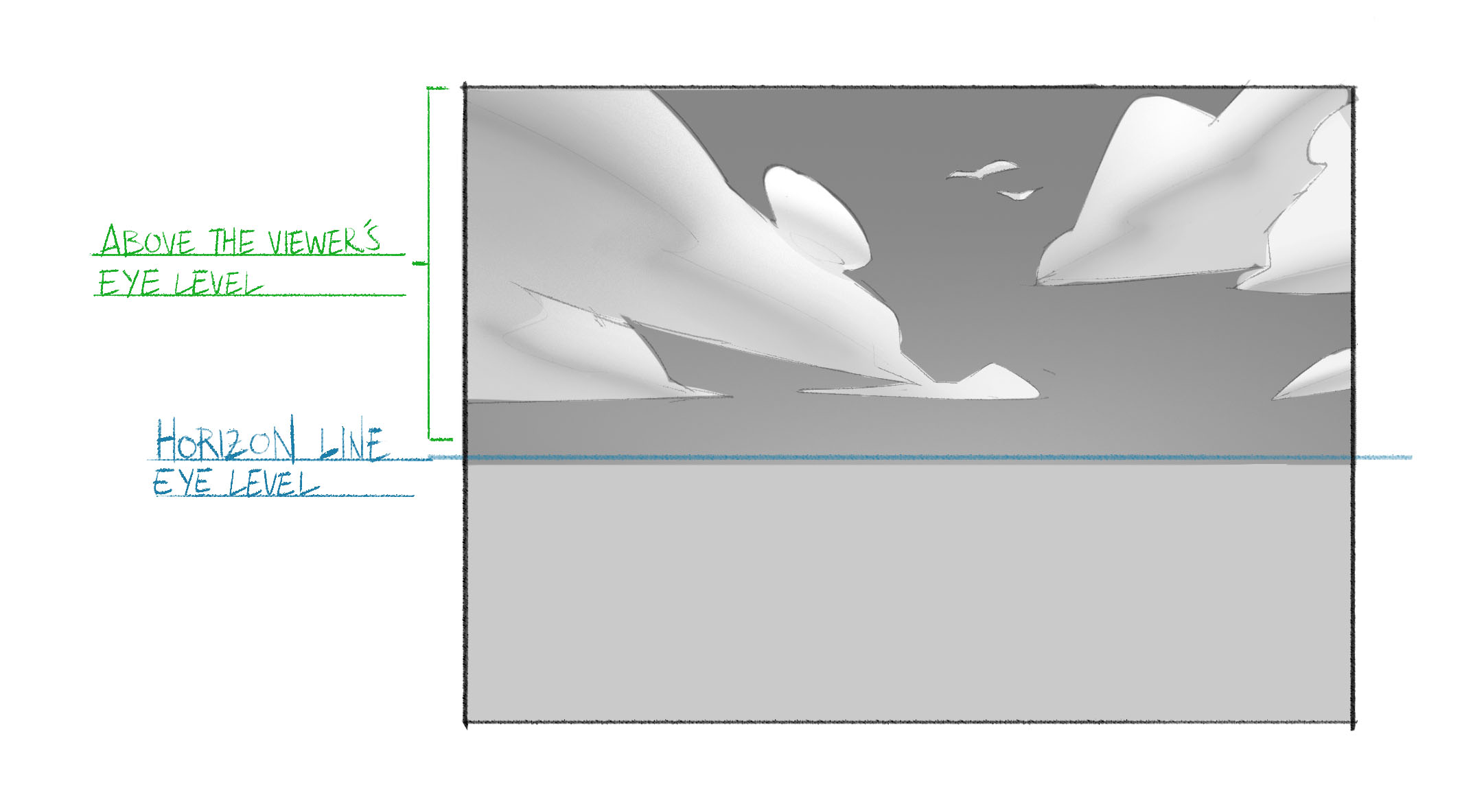

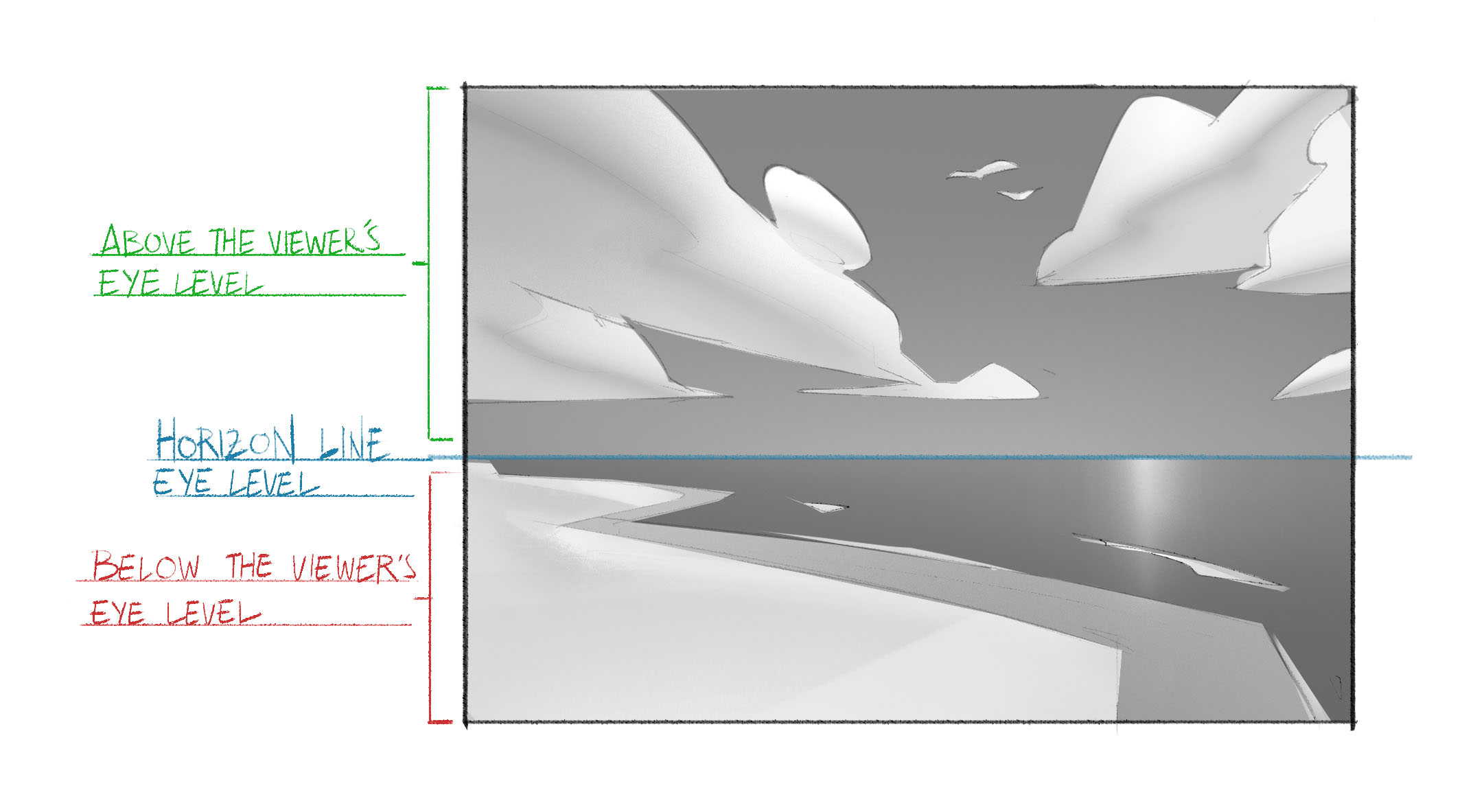

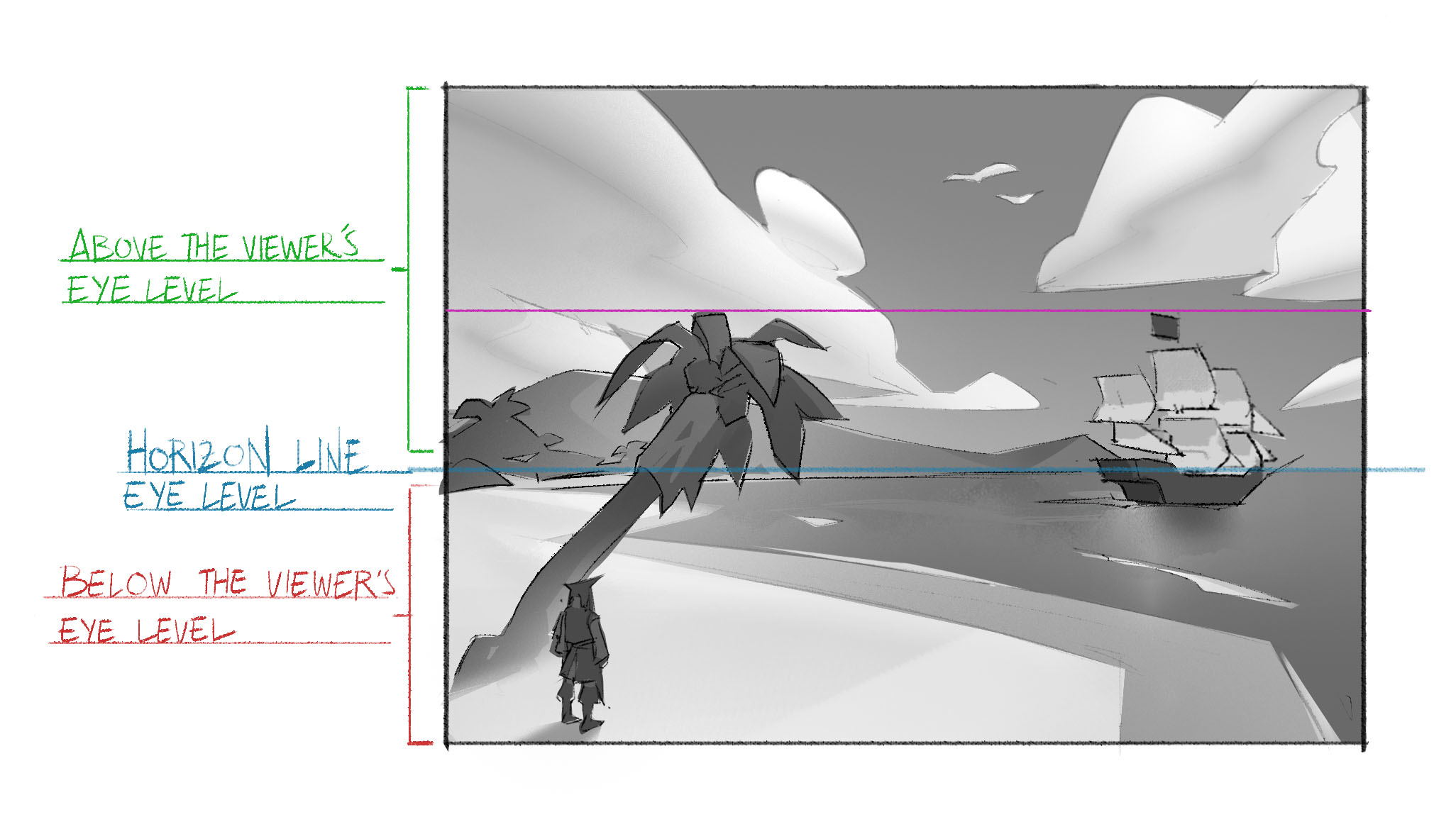

The concept here is straightforward. Everything above the horizon line is above the eye level of the viewer while everything below the horizon line is below the eye level of the viewer.

Some things that we might find above the horizon line are clouds and birds in flight.

Some things that we might find below the horizon line are the ocean, a beach, and a few scattered waves.

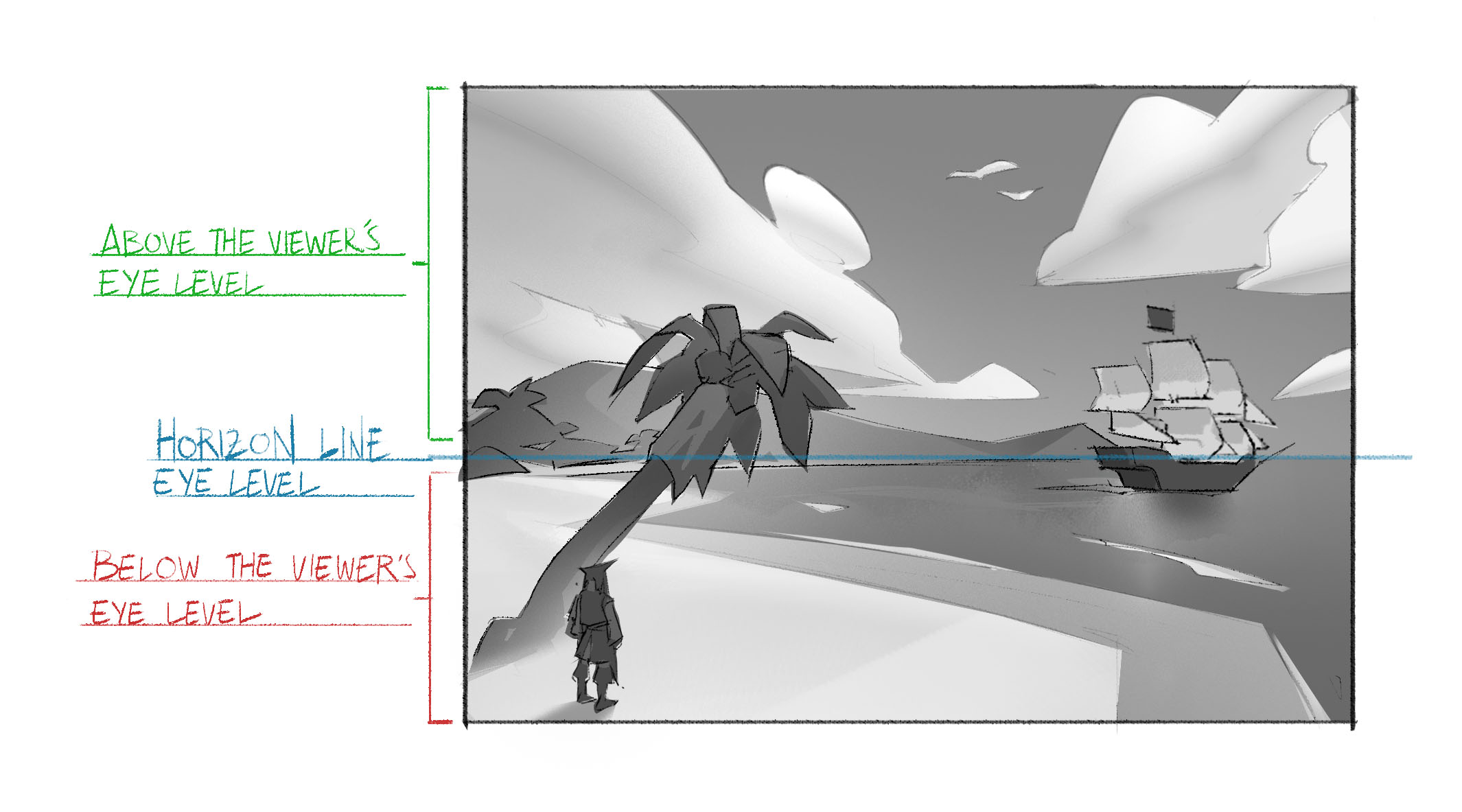

When objects overlap the horizon line, a part of the object is below, a part of the object as at, and a part of the object is above eye level.

Here are a couple of objects that overlap the horizon: some distant hills, a palm tree and The Black Pearl. Note that none of them rest on the horizon line. Instead, they start below the horizon line and extend above it. To start an object on the horizon would be impossible, because the horizon is infinitely far away.

This is pretty basic stuff - many of those reading are already super familiar with this. However, I’ll move on to further explain specific mechanics of how it works.

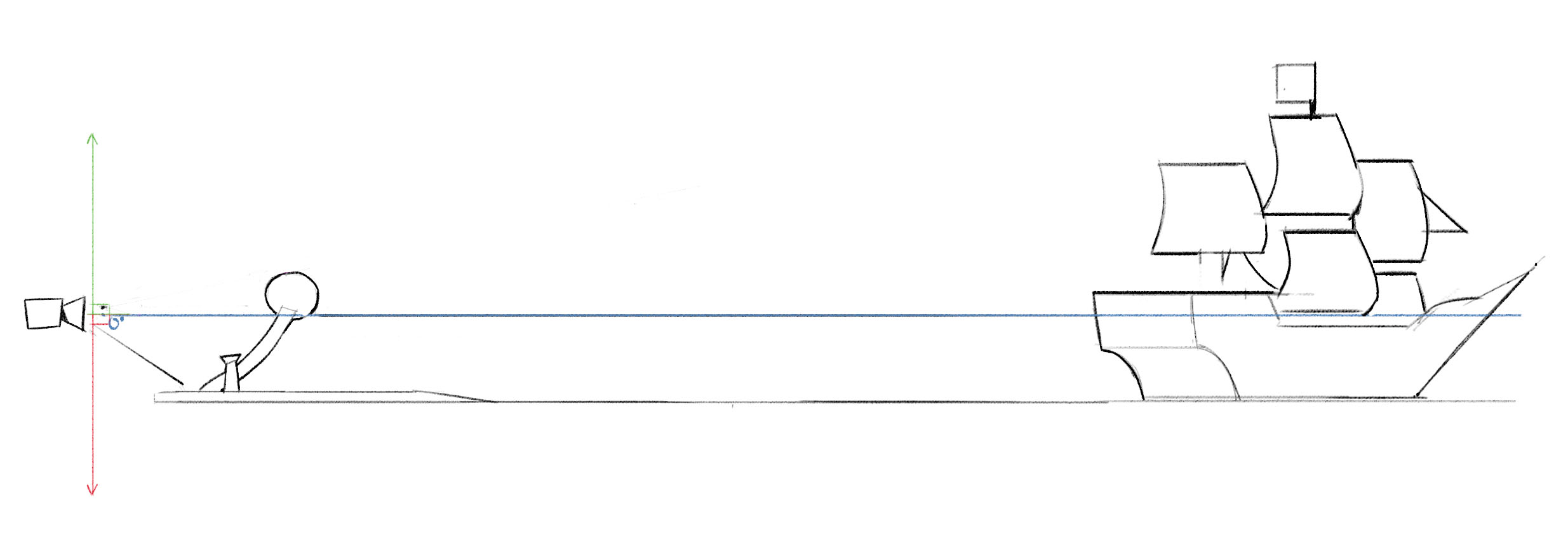

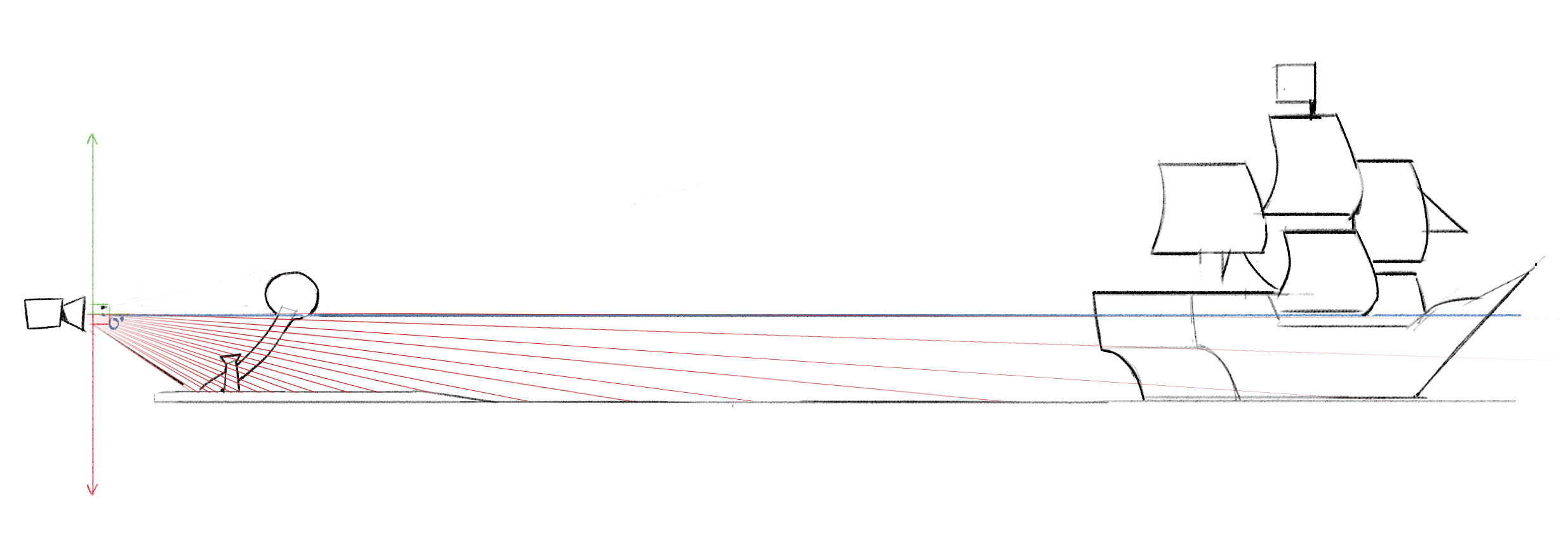

Let’s have a look at our setup for this shot.

The camera is on the left and the blue line that’s level with it is the eye level of the camera. Note that this line intersects the palm tree and The Black Pearl at the same height as the horizon line does in the final shot.

In other words, the horizon line is the same as the camera’s eye level.

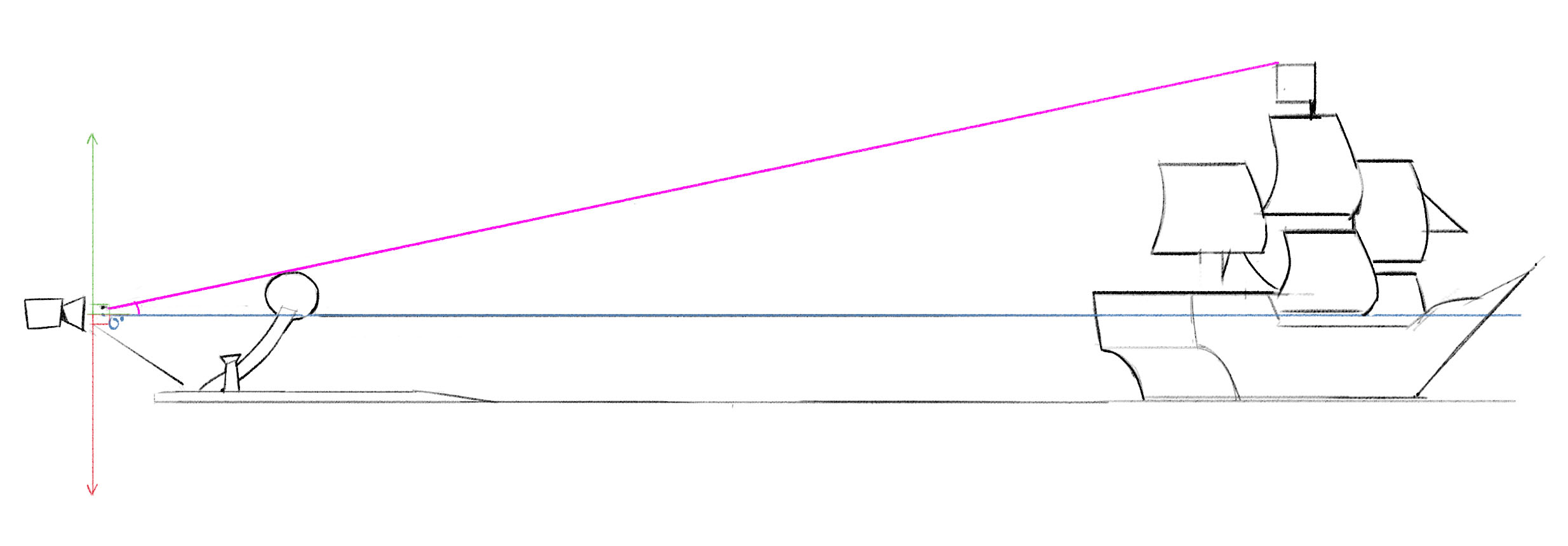

Let’s shoot a line out from the camera at an angle. Observe that this angled line hits both the top of the palm tree and the top of the ship:

When we look at our final frame, we see that these two elements actually line up together here as well:

Because the top of the palm tree and the top of the ship are at the same vertical angle from the camera, they end up on the same vertical height in our image!

As it turns out, the angle between any point and our camera tells us where that point is going to end up in our image. I know this might seem useless, but trust me, it becomes important later when we’re figuring out how vanishing points work.

Finally, let’s take a quick look at why the horizon line is the same as eye-level. It’s pretty simple. If I shoot any angle out from the camera that’s below eye level, it’s always going to be traveling slightly downward. Eventually, it’ll hit the ground (or in this case, the ocean).

Similarly, if I shoot an angle up from the eye-level, it’s going to travel upwards no matter how slight that angle is, off into the sky. The only line that will go neither up nor down is the line that shoots straight out of the camera, or the eye-level line. That line will hit the horizon, between the ground and the sky. It’s a little weird. but once you’re able to wrap your head around that idea, it’s obvious that the horizon line and eye level are the exact same thing.

So that’s it for the very basics. From this fairly simple foundation, we have the means to build out some super complicated stuff. First, though, we’re going to have to look at some other concepts, starting with vanishing points.